“I don’t know whether there are any moral saints. But if there are, I am glad that neither I nor those about whom I care most are among them. By moral saint I mean a person whose every action is as morally good as possible, a person, that is, who is as morally worthy as can be. Though I shall in a moment acknowledge the variety of types of person that might be thought to satisfy this description, it seems to me that none of these types serve as unequivocally compelling personal ideals. In other words, I believe that moral perfection, in the sense of moral saintliness, does not constitute a model of personal well-being toward which it would be particularly rational or good or desirable for a human being to strive.” - Susan Wolf, Moral Saints.

A moral saint, as this essay will treat the concept, refers to an individual who completely and consistently applies the tenets of a given moral philosophy. In this, these moral saints serve as physical embodiments of these transcendental ideals. An impartial, strong-handed general willing to sacrifice themselves and a thousand soldiers to ensure the safety and happiness of thousands more, regardless of personal feelings, for instance, might serve as a moral saint of utilitarianism, as could a charitable pauper living in destitution to entirely dedicate their resources to others. By the same token, there could be moral saints for whatever moral philosophy one wishes to imagine, though, for the sake of brevity and scope, this essay will largely discuss the concept in reference to utilitarianism.

In Moral Saints, Susan Wolf comments that she is glad that neither she nor anyone close to her is such a moral saint’ as she posits being a moral saint does not constitute a path towards “personal well-being,” a claim with which I largely agree. In this essay, I will demonstrate how moral saintliness is not necessarily a path toward well-being and, in fact, may not be conducive to it at all, illustrating Wolf’s concerns. I will also refute arguments against this thesis, showing that an obsessive and ‘perfect’ moral life may not be a good life. Finally, this essay will discuss the implications of this conclusion.

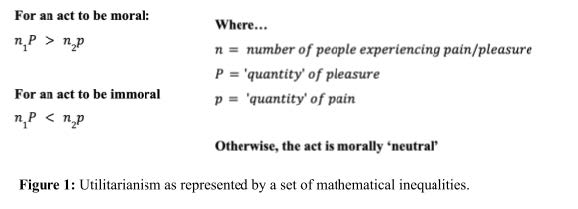

The moral philosophy of utilitarian thought revolves around the central harm principle: That one should maximize pleasure for the greatest number of people, with pain subtracting from pleasure, though these subjective experiences are largely unquantifiable. Therefore, an action causing a degree of pain to one person but pleasure in equal measure to two people would be a moral action. This principle is broadly illustrated below in Figure 1. To be a moral saint, one must uphold this central concept in all of one’s actions. As one can likely imagine, this would place a great burden upon the moral saint, as this essay will discuss.

Following this utilitarian framework, well-being will henceforth refer to a personal state of pleasure, that is, a state in which the pain one experiences does not outweigh the pleasure one experiences. As such, a ‘good life’ is one lived in a state of well-being.

In cases in which the complete upholding of a utilitarian principle requires moral saints to harm themselves to guarantee pleasure for a greater number of people, this would manifest as a physical burden of pain. This is not to say that a moral saint would be required to endanger themselves constantly; in fact, the everyday utilitarian sacrifices of such an individual would likely be simpler—work in a community garden at the cost of a sore back the next day, for instance—but that at some point, it would be required by circumstances. If a war were to break out against a vile enemy, such that by fighting and killing, the moral saint would maximize happiness for the greatest number of people, then the saint would be compelled to enlist. And if, during their tour of duty, a grenade were to roll towards their platoon, the saint would be compelled to leap atop it to absorb the explosion, minimizing group harm at the cost of grievous personal harm. Evidently, the consistent application of such principles across all situations that could occur in life exposes the moral saint to great danger and pain. As a result, an individual concerned with the moral saint’s well-being, as Wolf claims to be, would be reasonable in regretting the saint’s adherence to a doctrine of moral perfection.

Objectors to this line of reasoning would argue that because of their virtue, moral saints would derive happiness from their charitable and sacrificial acts, something to which I only partially agree. On a biological level, it is true that engaging in charitable behavior and helping others releases dopamine, serotonin, and other ‘positive’ emotional hormones, leading to a degree of pleasure in self-sacrifice. However, dopamine and serotonin can only go so far as to counteract pain. Yes, the previously mentioned gardening moral saint’s potential back pain would likely be counteracted or even nullified by the happiness of having helped others, but this happiness fails to counteract more serious or lasting physical pain. As this pleasure in self-sacrifice is biological in its origins, it is also limited in its duration, as our bodies cannot indefinitely produce positive emotional hormones—doing so would disrupt the critical hormonal balance. A moral saint torn apart by a grenade or shot valiantly in combat may, at the moment, feel similar happiness and pride in their heroic, moral act. However, while this hormone-induced happiness inevitably fades, the injury remains for the rest of the saint’s life, causing chronic pain and suffering. This is reflected in the disproportionately high suicide rates for military veterans and, in particular, injured or disabled veterans, highlighting how the self-sacrificial instinct that would motivate soldiers to fight for their country fails to protect them to the pain of doing so. Even a less extreme experience of physical harm would cause pain outweighing pleasure. Imagine intervening in a one-sided fight to defend a helpless victim and saving them at the cost of a black eye. It would be a much smaller physical cost, but still, despite the pride one would feel for preventing greater harm to the victim, one would almost certainly still experience the throbbing pain of the injury, demonstrating the fairly low limit for our biological ‘pleasure in pain’ mechanism.

In the cases where the moral saint would be compelled to sacrifice others to maximize collective benefit, their burden is psychological in nature. Take, for example, the hypothetical story of a man who, on his way to work, sees his daughter’s school bus crashed and in flames on the side of the road. The bus can only be entered from the front, and he knows that his daughter sits at the back. In the time it would take him to save his own daughter, he knows he could save a dozen children from the front of the bus. In this scenario, if he were a moral saint, the man would be compelled to sacrifice his daughter and save the dozen children, causing great tragedy to his family but averting it for the families of the twelve survivors. Even though the man, a moral saint, may know at heart he made the moral choice, a net positive of eleven happy families, he still must cope with the feelings of loss and guilt that he would feel as a parent, feelings that are deeply programmed into humans. As mentioned previously, these psychologically challenging yet moral decisions would likely not be everyday fare for a moral saint. However, given that moral saints must universally apply their moral principles and these scenarios are possible, they serve as scenarios that the saints would be compelled to take the ‘hard choice’ in. Because of this psychological struggle that moral saints would therefore be exposed to, they would experience emotional pain. This pain is also seen in veterans, who, in their service, are forced to make decisions that sacrifice others; in addition to chronic pain, another key driver for their heightened suicide rates is the experience of PTSD and guilt over lost comrades. Therefore, moral saintliness is not conducive to psychological well-being either, meaning that Wolf would be reasonable in expressing concern over it.

Demonstrably, across the body and the mind, the burden of being a moral saint leads to personal pain outweighing pleasure despite maximizing it for the greatest number of other people. Therefore, the model of moral saintliness does not constitute a suitable model of personal well-being. As a result, Wolf’s argument is understandable and justified in expressing concern for those who embody moral perfection in the sense of moral saintliness. Even if utilitarianism, as an example, is replaced by another moral philosophy, Wolf’s ultimate conclusion still stands. Although different schools of thought greatly disagree on what specific actions are moral, they do widely agree that disadvantaging oneself for the benefit of others is at the core of moral behavior. Consequently, regardless of the philosophy a moral saint embodies and consistently applies, a moral saint sacrifices themselves for the benefit of others, serving as grounds for humanitarian concerns such as Wolf’s.

Those who object to this conclusion would point to the societal implications of Wolf’s suggestions, that is, what would happen if her advice was universally followed; what would happen if there were no moral saints? These arguments are raised to suggest that without moral saintliness or perfection, our world, following Wolf’s counsels, would lack moral virtue. To that, I highlight that nowhere in her argument does Wolf advocate for or mention abolishing moral standards; instead, she simply opposes overly restrictive ones, as represented by moral saints’ perfection. Therefore, if, as the counterargument suggests, Wolf’s counsels were to be followed by all individuals, the world may lack moral saints, but it would still possess morally virtuous, if imperfect, people acting morally, if inconsistently. It would be a world with normal people who, following their aforementioned biological hormonal incentives, would act to maximize collective happiness whilst also experiencing personal well-being as a result of their charitable actions, representing a balance between the two.